Ed (the other cat, not the husband), was here a moment ago, looking to share in the ice cream ritual that I inherited from my mother. He has become a true Rubinstein even though his contact with my mother has been limited.

My mother still has ice cream before bed each night--vanilla is the preferred flavor these days. I remember her telling us of a recurring dream in which she was driving a car (gods forfend !!), and couldn't figure out how to make it stop. "Call Sam (my father)!", she shouted, and the car ran into the wall of a building which turned out to be an ice cream factory. She had to eat her way out.

I remember (vaguely) waking my brother in the middle of the night when we were kids (sometimes he woke me first), and taking turns walking out into the living room in our jammies, whining "I can't sleep!" while pretending to rub ostensibly sleep-deprived eyes with a tiny fist. Five minutes later, the other sibling would arrive on the scene with a similar complaint, and "of course!", the only possible resolution was ice cream ordered from some neighborhood store that would deliver pints of Hagen Dazs--coffee for us, and cherry vanilla for my dad. Mom ate most any flavor as I remember, and would finish any ice cream that was left in our dishes. We would argue over who got "the duck" which was the top layer of ice cream in the pint, shaped by the contact of the lid with the contents. Somehow that was the best tasting part.

Like most family stories, this tale may be apocryphal, but it is one of the links to childhood that endures many decades later. It has emerged in the last few months as a reminder of things that shaped me in long forgotten ways. I have been thinking about rituals a lot lately, especially as so many of mine appear to be breached by travel. But traveling back and forth between MA and VT and NYC has evoked memories of summer weekends in the car to and from the beach. We went to the same strip of sand every summer from the time I turned one, to when I was old enough to be living on my own. We pulled the little red wagon from the boat dock to the house and chained it in the same place at the ferry dock when we returned at the end of the weekend.

Every Friday night, my father would cut carrots and celery into sticks, my mother would make her "glop" with some assembling of mayonnaise or cottage cheese or yogurt and ketchup, and we would eat hot dogs and burgers on the grill. On Saturday, we had my father's char-broiled steak made according to a ritual that lasted decades: the coals in a pyramid toward the middle of the grill, the lighter fluid allowed to soak for 30 seconds, the flame starting toward the back and 20 minutes of burning to embers before the steak was set to cook. Of course, we walked into town for a movie and an ice cream cone each weekend, at least once.

It seemed normal then, the hour and a half trip to the beach, the half hour ferry ride, the ten minute walk to the house with the suitcase-loaded wagon, each Friday night. It seemed normal then, to wake when we returned to New York, under the yellow street lamps at the park, before we were carried half sleeping from the back of the car to the apartment I had known all my life. It seemed normal to take long drives in the country to a restaurant and to places that probably formed some liminal memory of rural locales that has imprinted me into adulthood.

It seems less normal now.

Maybe it is that I am the one taking on the burden of packing and unpacking; maybe it is that I am often traveling alone. Maybe it is that when I arrive in MA or NYC, I don't feel that I am at home.

Though many of those trips are to the same apartment I grew up in, though many of those trips are to the same place where the banging of the steam heat in the radiators was the music that I slept to; though many of those trips are to the apartment with the same green walls and the same green and white kitchen, and the same nighttime view over the park, I am increasingly feeling the distance grow from a place that will never again be my home. When Mom leaves the apartment for the last time, I will spend some weeks packing the boxes of papers and books and deciding where the furniture will go. After all, she has only rented that apartment, the one that patterned our family for more than 65 years, and the landlord will want it back...quickly.

I will probably close the house in Fire Island as well. I will pack up the furniture and the linens and ship them to Vermont. I will pack up the hibachi that my Dad used to make those steaks, and the bowl my mother used for her glop. I will sweep the sand from the floors into a little bottle that I will carry with me; I will add some ocean water and seaweed and perhaps a few shells.

In New York, I will say goodbye to the doormen; Joe, who wore a blue wool coat every day even in the heat of a New York summer, has been replaced by Umberto, and Mike by Cirillo, but these men started and ended my days--in reality or in my imagination, even when I no longer considered this my home.

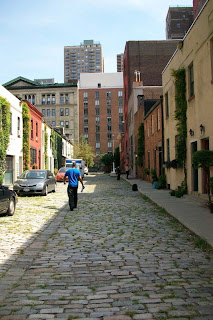

I haven't planned what I will do on that last night in New York, but there was one ritual that would have probably been part of that last night in New York. One of my strongest memories of childhood, as strong as waking under yellow lights, is of walking on the cobblestones of Washington Square Mews, a street that once ran beside the 19th century carriage houses that served the brownstones on Washington Square Park.

I remember pulling away from my mother's hand, so that I could walk on those uneven pavers, and feel their wobbles under foot.

I understand that the recently completed renovation of that street that ran between one and two story square brick and stucco structures, has resulted in a smooth paved surface.

I wonder, once the apartment door has closed for the last time, once the hibachi is packed and gone, what will remain of the rituals that shaped me. If I have not lived in New York for more than a decade, in that apartment for more than three, I could always check back in; insert myself for a moment in the familiar. The view outside the apartment in New York is unchanging, over the Park and to the Empire State Building. New architecture is like some decision to repaint the walls or move the cabinets; it doesn't fundamentally change what we see or know. But that view is about to belong to someone else, and I will be a passing tourist in the place I learned to walk. And I suspect that over time, the surface of my memory will be smoothed like those cobbles.

I once believed that I could never find a home because I was tugged between place and passages, but there was always that view, and the sand. I grew up with passages between landscapes as different as it was possible to be, but those landscapes were burnished in celery and carrots on Friday nights, and ice cream before bed. They were both the canon and the apocrypha.

Now the canon of childhood will be gone, leaving only the apocrypha.

I have lived a life that is rare these days-- a life where the places of my childhood autobiography, remained intact long into an adult life lived away. Perhaps I am feeling for the first time, a kind of homesickness, not for the place itself, but for the taste of ice cream before bed, and the feel of the sand and cobbles under foot, and what that meant in a world of change.

Vermont is a place of ancient stone walls that have survived change. Perhaps I will repair the walls that remain from the past. Perhaps I will start a new one, one rough stone at a time.

{Note: This post has languished for many weeks, unposted. I have not felt that the ending was the one I wanted. Then, this morning, I realized, the ending is not yet written. I suspect there will be a sequel.]